When your vacation plans start to dissolve, a little flexibility can go a long way, and may even provide you with the opportunity to see natural wonders rarely witnessed by the majority of travellers. This is the story of how we got to see magnificent wetlands and wildlife as well as the results of a jökulhlaups, and why you might want to consider spending an extra day or more exploring to the west of Anchorage.

We arrived in Anchorage from Gustavus (via Juneau) on our penultimate flight with Alaska Airlines on 3rd August.

After a great week down in south east Alaska, where we’d been extremely lucky with the excellent weather, the skies now decided that ‘blue’ and ‘calm’ were over.

Having reserved a couple of slots with Ellison Air at the end of April, we had hoped to flight-see to the north of Anchorage around Denali (a.k.a. Mt. McKinley, as it was then still officially titled) and Prince William Sound to the south east in whatever order the conditions best suited on the 4th and 5th. As it turned out we wouldn’t get to see either destination on this vacation.

We’d booked accommodation at the Holiday Inn Express because it had a free shuttle from the airport, we could use IHG points to pay for our room, and, most importantly, it was really close to Lake Hood, the “largest and busiest seaplane base in the world”.

Our scheduled flight departures were both for 08:00 because “the mornings usually have the smoothest air and that is a big deal on a long over land trip like McKinley”, but, when we made the 0.2 mi./3 min. walk from the hotel to Ellison Air’s office on Wisconsin Street at the eastern end of Lake Hood (formerly Lake Spennard until a canal was dug to connect the two water bodies), the weather forecast for the day dictated that flights to Denali and Prince William Sound were untenable.

There was still a window of opportunity to take off to the west of Anchorage, and so, with no knowledge of what lay along the top of Cook Inlet, we agreed to the offer to take us out on a more ‘local’ flight and a landing on Beluga Lake beneath the Triumvirate Glacier. Although we didn’t know it at the time, this flight would take us over the rich wetlands and coastal waters of Matanuska-Susitna (Mat-Su) Borough, and, intermittently, into Kenai Peninsula County as we flew up the Beluga River.

![The area of our trip from Anchorage to Beluga Lake [Base terrain map data © 2016 Google].](http://www.afewmilesmore.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Anchorage-to-Beluga-and-Strandline-Lakes-1.png)

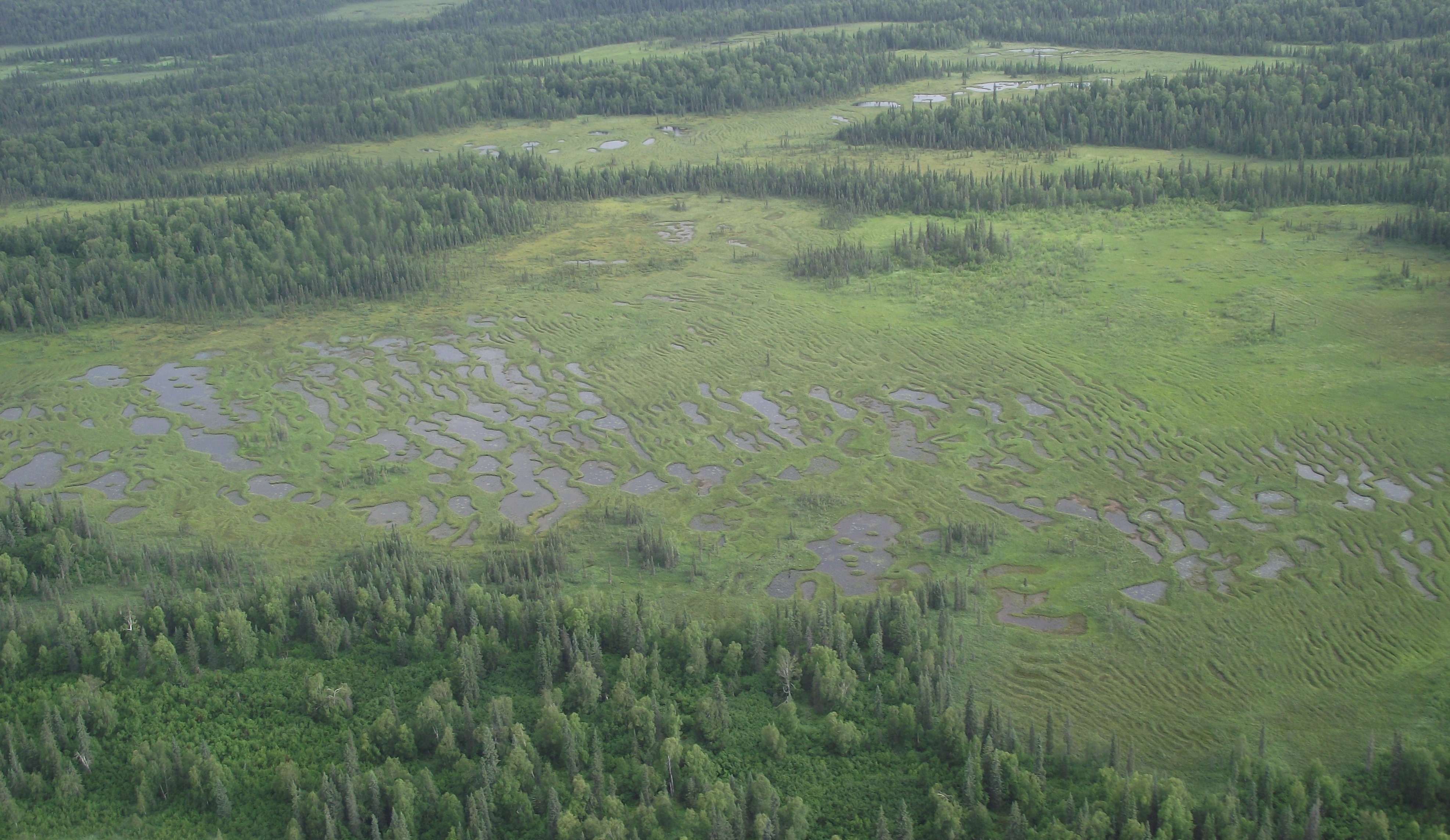

After briefly following a course parallel to the power transmission lines that stretch from the Beluga River Power Plant to supply Anchorage with nearly half of its electricity, we turned towards the lower reaches of the Susitna Flats, spotting our first bull Moose (Alces alces) of the day by the forested banks of one if the myriad of creeks and small rivers flowing down to the sea.

The Susitna Flats State Game Refuge is a 300,800 acre (121,729 ha) refuge created 1976:

“Birds

Perhaps the most spectacular feature of the Susitna Flats State Game Refuge – and certainly the prime reason for its refuge status – is the spring and fall concentration of migrating waterfowl and shorebirds. Usually by mid-April, mallards, pintails, and Canada geese are present in large numbers. Peak densities are reached in early May when as many as 100,000 waterfowl are using the refuge to feed, rest, and conduct their final courtship prior to nesting. The refuge also hosts several thousand lesser sandhill cranes and upwards of 8,000 swans. Northern phalaropes, dowitchers, godwits, whimbrels, snipe, yellowlegs, sandpipers, plovers, and dunlin are among the most abundant of shorebirds. Most of the ducks, geese, and shorebirds move north or west to nest in other areas of the state. About 10,000 ducks -; mostly mallards, pintails, and green-winged teal, remain to nest in the coastal fringe of marsh ponds and sedge meadows found in the refuge. Recently, Tule geese, a subspecies of the greater white-fronted goose, have been discovered to nest and stage on Susitna Flats. In the fall, migrant waterfowl and shorebirds once again arrive in growing numbers to rest and feed on sedge meadows, marshes, and intertidal mud flats.

Mammals

Back from the coast are brushy thickets where moose calve each spring. In the winter, moose from surrounding uplands return to the refuge to find food and relief from deep snow. Both brown and black bears use the refuge, feeding particularly on early spring vegetation near salt marshes and sedge meadows. Beaver, mink, otter, muskrat, coyote, and wolf can also be found. Trapping is a regular winter activity on the refuge.

[…]

Fish

The Susitna River and its tributaries support the second largest salmon-producing system within Cook Inlet. In the summer, set net fishing sites dot the shoreline of the refuge.”

[Source: ADF&G]

![The area covered by the Susitna Flats State Game Refuge. [Source: ADG&F]](http://www.afewmilesmore.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Susitna-Flats-State-Game-Reguge-Matanuska-Susitna-Borough-Mat-Su-Cook-Inlet-Anchorage-Alaska.png)

[Source: ADG&F]

Along the shoreline mud bars we started to see increasing numbers of lounging seals, and were also lucky enough to spot the distinct white shapes of Beluga Whales (Delphinapterus leucas) in the grey waters close to shore, which is not a privilege we’d have had around Denali. The resident population of Belugas in Cook Inlet means this is one area where viewing is common, particularly in summer and fall when they congregate between the Little Susitna and Susitna Rivers, before they move to deeper waters slightly further south around Kachemak and the Barren Islands during the winter.

Aside from all the wildlife, this area is not always devoid of inhabitants. At the edge of the lake near the center of the image below, a small cabin can just be seen, and, as marked on the earlier map, it’s not the only one in the refuge. This area is prolifically fished and hunted:

“An impressive 40,000 user-days of sport fishing effort are expended on the Little Susitna River each year, reached over land on a rough 4-wheel drive trail. Some hardy fishermen head for the Little Susitna by boat from the mouth of Ship Creek.

The Theodore and Lewis rivers are popular fly-in fishing streams for king salmon from late May through June. Combined, these rivers annually provide approximately 7,000 user-days fishing effort and a harvest of 1,000 king salmon.”

[Source: ADF&G].

“Each year approximately 10 percent of the waterfowl harvest in the state occurs on Susitna Flats, with about 15,000 ducks and over 500 geese taken.”

[Source: ADF&G].

After a few miles more of the spectacular coastal wetlands we turned inland to the northwest and re-crossed the transmission power lines as we headed to the Beluga River and Lake for our scheduled landing.

The landscape beneath us remained consistently diverse and just as riveting.

In the open spaces of creek gravel bars we spotted more moose and a bear using the natural highways, but we soon reached our destination

Beluga Lake lies 56 mi. (90km) WNW of Anchorage. It is principally formed by the meltwaters of the Triumvirate Glacier which primarily flow along the northern and southern flanks of a 4.5 mi. (km) bar of land which separates the lake and the glacier’s frontal moraine at the west of the lake. Beluga Lake is approximately 6 mi. (10km) long from east to west, and about 3 mi. (5km) wide. The Beluga River starts at the eastern end of the lake with additional in-flow from the tributary Chichantna River (fed in turn by the Capps Glacier) in the south-eastern corner of Beluga Lake. Coal Creek flows into Beluga Lake from the north just before the start of the river. The relatively isolated location is reflected in the USGS topographical map which dates back to 1958, but it still provides a reasonably accurate impression as can be seen on the CalTopo website.

In a video posted the day before our flight, a landing on Beluga Lake by a 1958 De Havilland Canada Beaver DHC-2 MK.1 floatplane from Rust’s Flying Services shows what the area around the Triumvirate Glacier and a Beluga Lake landing look like in good weather.

As we reached Beluga Lake it became apparent that something strange had recently happened to the landscape below us.

![Heading west, looking south. Beluga Lake with the start of the Beluga Rover to the left, with the Chichantna River flowing left to right in the background.]](http://www.afewmilesmore.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Beluga-Lake-and-the-Chichantna-River.jpg)

![The flooded shoreline where Coal Creek enters Beluga Lake.]](http://www.afewmilesmore.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/New-shoreline-at-Coal-Creek-Beluga-Lake-Alaska.jpg)

We’d already witnessed the beautiful colour of consolidated glacial ice and the impressive calving of tidewater glaciers in SE Alaska, but the impact of this sight and recognition of the scale of this natural catastrophe was simply awe inspiring.

According to the U.S. Board on Geographic Names the Triumvirate Glacier was so named by S. R. Capps and R. H. Sargent of the U.S. Geological Survey “because this glacier is composed of the joining of three large glaciers.” It flows for over 20 miles in a south easterly direction down towards Beluga Lake, and, near the glacier terminus, a north facing lobe Strandline Lake, forms an ice-dam to the outflow of Strandline Lake in its high-sided narrow valley.

As Strandline Lake backs up and rises against the glacier lobe, calving fills the lake with icebergs that can be 120m in height. Eventually the hydrostatic pressure is sufficient to float the lobe and the water variously forces its way over the ice, down plunge pools, and through old subterranean channels in the bedrock at the northern edge of the ice, whilst also carving its way along new routes and the underside of the glacier.

This type of cataclysmic outflow is known by the Icelandic term ‘jökulhlaups’, which in English means a glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF). We’d never heard of it, let alone witnessed the results of such a catastrophic environmental event.

In the earlier video, Strandline Lake is featured from 4’ 14” to 4’ 57”. At the point when it was filmed the lake was full and the Glacier was displaying characteristic pre-jökulhlaups glacier surface water pools. Shortly before our arrival this condition had dramatically changed, but, if we hadn’t taken the chance to head out in a previously unconsidered direction, we’d probably still know nothing of such events.

The month after our visit this video was posted showing a view of the devastation from a R44 helicopter:

A more detailed description of how Strandline Lake is repeatedly blocked and the resulting release and refill mechanisms can be found in the very easily read “A History of Jökulhlaups from Strandline Lake, Alaska, USA” by Matthew Sturm and Carl S. Benson (Journal of Glaciology, Vol.31, No. 109, 1985). Given the publication date, it naturally enough focuses on the September 1982 jökulhlaups when it was calculated that over 95% of Strandline Lake had drained out, releasing about 185 billion gallons (700 million m3) of water, although it is estimated from earlier strandlines that previous releases could have been up to 65% greater by volume.

Other online literature is, unsurprisingly, sparse, but while Sturm and Bensons’ historical (1940 to 1982 (and 1984)) investigations show a release frequency of every 1-5 years, anecdotal and video evidence suggest that an annual release is possibly now more the norm.

In 2013 National Geographic Channel TV viewers might have watched episode 3 of the first series of “Ultimate Survivor Alaska” which was titled “Into the Void” []. It was filmed in the Fall of 2012, and shows that Strandline Lake (see 24’25” to 34’38”) had been recently drained (and why you might not want to be down there crossing it on foot).

The year after our visit Strandline Lake was once again captured on video in a pre-jökulhlaups condition during the flight in a Cessna 180H floatplane into Beluga Lake posted in July 2014:

In a video uploaded in early August 2014, another R44 helicopter flight recorded post-jökulhlaups conditions:

Given the weight of video evidence in this post, travelling to Beluga Lake is clearly not restricted to grey days. Nor is it restricted to summer months and floatplanes, but you might want to consider the following statistics in planning whether your fly-in uses floats, skis or wheels to get down at Beluga Lake:

| Year | Freeze Start | Freeze Final | Breakup Start | Breakup Final |

| 2002 | 26/10/01 | 01/11/01 | 30/05/02 | 30/05/02 |

| 2003 | Latest – 13/12/02 | Latest – 19/12/02 | Earliest – 13/05/03 | Earliest – 18/05/03 |

| 2004 | 09/11/03 | 19/11/03 | 17/05/04 | 04/06/04 |

| 2005 | 03/11/04 | 20/11/04 | 23/05/05 | 23/05/05 |

| 2006 | 03/11/05 | 06/11/05 | 23/05/06 | 30/05/06 |

| 2007 | 31/10/06 | 09/11/06 | 21/05/07 | Latest – 08/06/07 |

| 2008 | 08/12/07 | 08/12/07 | Latest – 01/06/08 | 01/06/08 |

| 2009 | Earliest – 24/10/08 | Earliest – 24/10/08 | 18/05/09 | 30/05/09 |

| 2010 | 08/11/09 | 10/11/09 | 29/05/10 | 29/05/10 |

| 2011 | 27/10/10 | 22/11/10 | 20/05/11 | 29/05/11 |

| 2012 | 05/11/11 | 05/11/11 | 21/05/12 | 02/06/12 |

| 2014 | 07/11/13 | 18/11/13 | 14/05/14 | 20/05/14 |

Freeze Start = first time lake at or greater than 10%. Freeze Final = first time lake greater than 90%.

Breakup Start = last time lake greater than 90%. Breakup Final = last time lake at or greater than 10%.

[Data from the NPS]

In addition to a check on the condition of Strandline Lake before landing on Beluga Lake, it’s probably also worth bearing in mind that these jökulhlaups don’t only occur in the fall. Click here for a link to images of the December 1980 Beluga River Outburst Flood, noting how far the destructive force of the water will travel.

The journey back was a more direct overland route and took under 40 minutes. Once again, the landscape was a mosaic of waterways and wetlands, with the trees also occasionally revealing cabins and landing strips as we re-crossed the Susitna River, before more managed pastures and small herds of cattle came into view.

Our round trip only took about 1.5 hours, but, when we landed safely back at Lake Hood, we knew that we had made the right decision to fly west that day, and that we’d been spectacularly rewarded with a once in a lifetime experience.

Aside from Ellison Air and Rust’s Flying Service (who don’t list this trip as a regular departure, so prices are on application) there are a number of other Anchorage based operations who offer flightseeing over this fantastic area, including

- Regal Air offer a 2 hr “Triumvirate Glacier and Mt. Spurr Volcano Flightseeing Tour” with a Beluga Lake landing and beach walk for $295 p/p . Regal Air operate from Lake Hood using a variety of aircraft equipped depending on the season.

- Sound Aviation charge $200 p/p for an approximately 1.5 hr “Volcano/Glaciers” flightseeing experience They operate from Merrill Field airport using asix passenger retractable wheeled landing gear Piper Lance.

- Trail Ridge Air offer a 60 min. “Discover Alaska” flight for $150 p/p from Lake Hood in a Dehavilland DHC-3 Beaver floatplane.