It was the 10th August 2013, and we’d almost reached the end of the road when we arrived in the ‘Halibut fishing capital of the world’. If, like us, you’re not into sea fishing, that might not sound like the most attractive destination advertisement, but I don’t mean it to sound like we’d had enough of the 49th state when we drove into Homer, Alaska. We were literally just about to run out of highway (and on the way there had passed by “North America’s most westerly highway point” at Anchor Point).

After a fantastic couple of preceding weeks in Alaska, we were exactly where we wanted to be as we drove down the Sterling Highway (Alaska Route 1, or AK1) and onto Homer Spit (which, with the longest section of road jutting out into an ocean in the world, gives you an extra 10 minutes of driving if you’re so inclined).

We were a mere 4,612 miles (7,422 km) from home as the intercontinental crow flies (and we were clearly tourists in that we were measuring distances in miles first rather than by hours), but we’d travelled considerably further by air and land to get to our final-stay destination of choice in Homer during a three week vacation tour of Alaska in late July to mid-August.

Inspired by our first experience of viewing Brown Bears at Knight Inlet in British Columbia three years earlier, we’d decided to try and end our vacation with a similar highlight, and then have a few days of chilling out with no other trips booked or schedules to meet until it was time to head home.

Back at the start of the previous January we’d booked 3 seats (and by ‘booked’ I mean we’d paid the total amount of $1,950.00* in advance, not a reservation fee with the balance due at a later date or on arrival) with K-Bay Air to fly our family of three out to the Katmai National Park for a bear viewing day trip on the day after our arrival in Homer. As requested, we’d checked-in at their office on the day of our arrival and had been met with a friendly welcome, and instructions where to meet at Homer airport the following morning at 08:00AM…

*I think we probably got the previous season’s rate as our initial enquiry had been in December 2012, which is worth considering if you plan ahead.

…but things didn’t happen quite as planned. Alaskan weather is notoriously changeable – and the second half of August was running true to form in that rainfall often increases then – but that all just serves to emphasise the sense that you’re on the edge of a true wilderness. In Alaska, towns as big as Homer (the name ‘City of Homer’ always makes me smile as it had a population of 5,310 in 2013) don’t really qualify as ‘wilderness’, but you can probably see it from where you’re sitting, and the weather can always bring you back to a healthy sense of your insignificance.

On the morning of our intended departure we rose reasonably early, avoided scented deodorants/perfumes after bathing, dressed in multi layered clothing with hats, gloves and spare socks stowed, and checked each other’s pockets for errant tuna sandwiches. We then made the 4.3 mile (6.9 km)/9 min. drive through the rain and mist down to Homer airport, where we were told we couldn’t fly yet, and that we should come back in an hour.

We drove back to our accommodation at Wild Rose Cottages, kicked our heels for 40 mins. and drove through the rain and mist down to Homer airport, where we were told we couldn’t fly yet, and that we should come back in an hour.

We drove back to our accommodation, kicked our heels for 40 mins. and drove through the rain and mist down to Homer airport, where we were told we wouldn’t be flying that day, and that we should report to the office on the Spit in an hour for a refund.

I totally get it that safety comes first, and that if the weather says you can’t fly, you can’t fly. I accept that if there is no availability to re-schedule in the next few days, it would be unfair to shunt other booked passengers. I really didn’t appreciate the total failure to express even the slightest modicum of regret on behalf of the company, the unwillingness to respond when asked to suggest any other companies who might be able to help out, and to then be presented with a paper cheque refund in US$ which we would be unable to cash until we returned home (even though we’d paid by visa all those months before). However, just because somebody else is having a bad week (and you never know what problems other people might be facing; I later came to understand why there might have been genuine reason in this instance) it doesn’t mean you have to let it affect you, and we suddenly had more important things to do.

You need to have a ‘Plan B’ (and probably a ‘Plan C’) for bear watching in Alaska. Our plan B consisted of having several days still left in Homer and a list of all the other bear watching flight companies in town.

Our first stop was Emerald Air Services on Lakeshore Drive, where, when we explained our predicament, we were kindly and sympathetically told they had no availability for the period of our stay in Homer. Maybe another time guys, looks like a great trip.

I have to admit that by now, and having already noticed a sign from another bear viewing flight company advertising availability after our departure date from Alaska, I had started to privately question whether I was going to be able to deliver on our hopes. A third of a mile further on we turned down Lampert Loop, parked up, and somewhat despondently walked down to the Beluga Lake office of Steller Air, where we were welcomed with smiles from company founder Mark Munro , flight coordinator Olympia Piedra and the rest of the team, and a ‘can do’ attitude that felt like a hug.

Steller Air is a small floatplane charter service based on the 3000 x 600 ft. (914 x 183m) Homer-Beluga Lake Seaplane Base (known by the FAA as the excitingly coded ‘5BL’). Their website, which is linked above, provides pretty comprehensive information about the services they offer – there’s no point in me copying it all here – and allows direct reservation enquiries. You’ll have to visit them in person to get a true grasp of their friendliness and the sense of optimism that this operation inspires.

We were offered a flight to Crescent Lake (not to be confused with the Crescent Lake just north of Kenai Lake on the Peninsula or Lake Crescent in Clallam County in the north of Washington State) in the Lake Clark National Park on the 13th for $1,797 for the three of us, which we of course accepted. For the next 36 or so hours we kept a weather eye on the skies. As we waited through the 12th, we visited the excellent Islands & Oceans Visitor Center of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, ate out at some great places (try the Boardwalk Bakery for breakfast, Maura’s Café for lunch (see below) and either the Fresh Catch Café or Captain Patties Fish House for dinner if you decide to visit Homer), and just relaxed around our rented house. On the afternoon before our intended new flight date the view across Kachemak Bay from the upper balcony of the Kelly House had some sunshine and encouraging streaks of blue in the sky.

By the following morning the world was looking a little too grey again.

We watched the gulls and a family of Trumpeter Swans down on Homer Spit before driving back to Beluga Lake, and had finished our breakfast burritos before we arrived, but remember that you will need to pre-declare your weight and it may be checked. Take a look at the Stella Air blog for an insight into Alaska floatplane life (and more on what’s available to see and do with Steller). In case it gets deleted in future seasons, I’ve quoted this post for posterity.

“Truth, Lies and Floatplanes in Homer, Alaska

On a floatplane ride, weights are important. We do a weight and balance of the aircraft to make sure that we are in the limits of a gross weight for a safe take off. Because of this, we ask every passenger their weight, or weigh them in the office. We also weigh a lot of gear. Because our flight coordinators ask a lot of people their weights, and then often have to weigh passengers when they come into the office, they have discovered an interesting fact in the course of loading floatplanes. Contrary to popular opinion, men lie about their weight more than women. Sure, a lady will not like to tell you how much she weighs, but she will discreetly whisper something close to the truth. Men, however, seem to boldly shout out a number that is often 30-40 pounds below their actual weight. Now boys, the girls in the office are working hard to get everyone and their gear to their Alaskan destinations—give them a number close to the truth getting everyone in the air will be a lot easier!”

Having arrived promptly at Steller Air for our safety briefing (and credit card payment), we prepared for departure. Our aircraft for the day was N77206, a Cessna U206G Stationair floatplane (the red floatplane that features strongly in many Steller publicity images is Mark’s Cessna TU206A). This was the second time in less than 10 days that we’d flown on exactly the same type of aircraft, attesting to the ubiquity of this type of aircraft in Southcentral Alaska, so we were already confident of the machine’s capabilities.

What really put us at ease was the quietly spoken integrity and professionalism of our pilot, Tom Young, but you can read more about this later, and we were just keen to get into the air and out to some bears. This Cessna 206 configuration has six forward facing seats in rows of two (including the pilot’s seat on the left), so I was seated next to Tom, and my wife and daughter were in the second row. The overhead wings provide for good downward visibility. If there’s something to see.

We reached the confluence of the Lake Fork Crescent River and the North Fork Crescent River (not that we could see it) and swung west in the direction of the lake. There was a brief two second sighting of the water ahead, and Tom said that he could probably get us down, and that there were less experienced pilots who would definitely go for it, but if we did go down he couldn’t guarantee we’d get out again. The tone was clear, so this was an easy decision, as we’d signed up to fly with people who know what they’re doing and to respect their advice. We turned back to Homer.

The return flight was a little surreal as we flew back in the narrow space between the cloud above and the fog below:

We even got in a spot of glacier viewing as we circled by Grewingk Glacier:

A hole in the fog appeared above Beluga Lake and we circled back for our descent to the water:

We now only had one day left before we had to start our homeward journey, so we had no hesitation in deciding to see if we could book another flight the following day. We were in for a shock. As we asked the question we were told that as they hadn’t got us onto Crescent Lake, Steller Air would be willing to try again the following day at no extra charge. Forget fancy words on websites and brochures. This is what a real commitment to customer satisfaction looks like.

It also demonstrates Steller Air’s commitment to passenger and pilot safety. Tom must have known what it would cost the company, but he hadn’t hesitated when he advised the return that day.

Olympia recommended Maura’s Café, and after we’d bagged the remains of our huge deli sandwiches – we’d taken the option of a side of soup for just $1 extra, and there was no way we could have finished all of the delicious first choices too – we strolled off down Bishops Beach.

By the late afternoon, as we watched Sea Otters and Bald Eagles around Homer Spit, the sky had turned blue.

From back up on East Hill Road the world suddenly started to look rather different, as we could see the sun shining on Beluga Lake, on houses at the far shore of Kachemak Bay, and glistening on the snow in the peaks above. That night a half-moon shone through thin cloud.

This photo from the following morning’s take off once again shows how quickly the weather can change in Alaska, and although some cloud had returned, this was much more like what we’d been hoping for:

Tom was our pilot again, and as we flew across the placid waters of Cook Inlet we could see small drilling rigs, and even smaller private boats leaving distinctive wakes. We apologised to Tom when Rachael decided to take a sleep break, but he just took it as a sign of a confident passenger:

![Rachael sporting her then new Alaska Geographic buff which has since become her standard accompaniment to any cold weather.]](http://www.afewmilesmore.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Stella-Air-flights-are-pretty-relaxed.jpg)

As I get to the bit where we headed inland into the Lake Clark National Park and Preserve (NP&P) again, it’s worth reflecting on the size of the area of which we were about to experience a tiny slice…

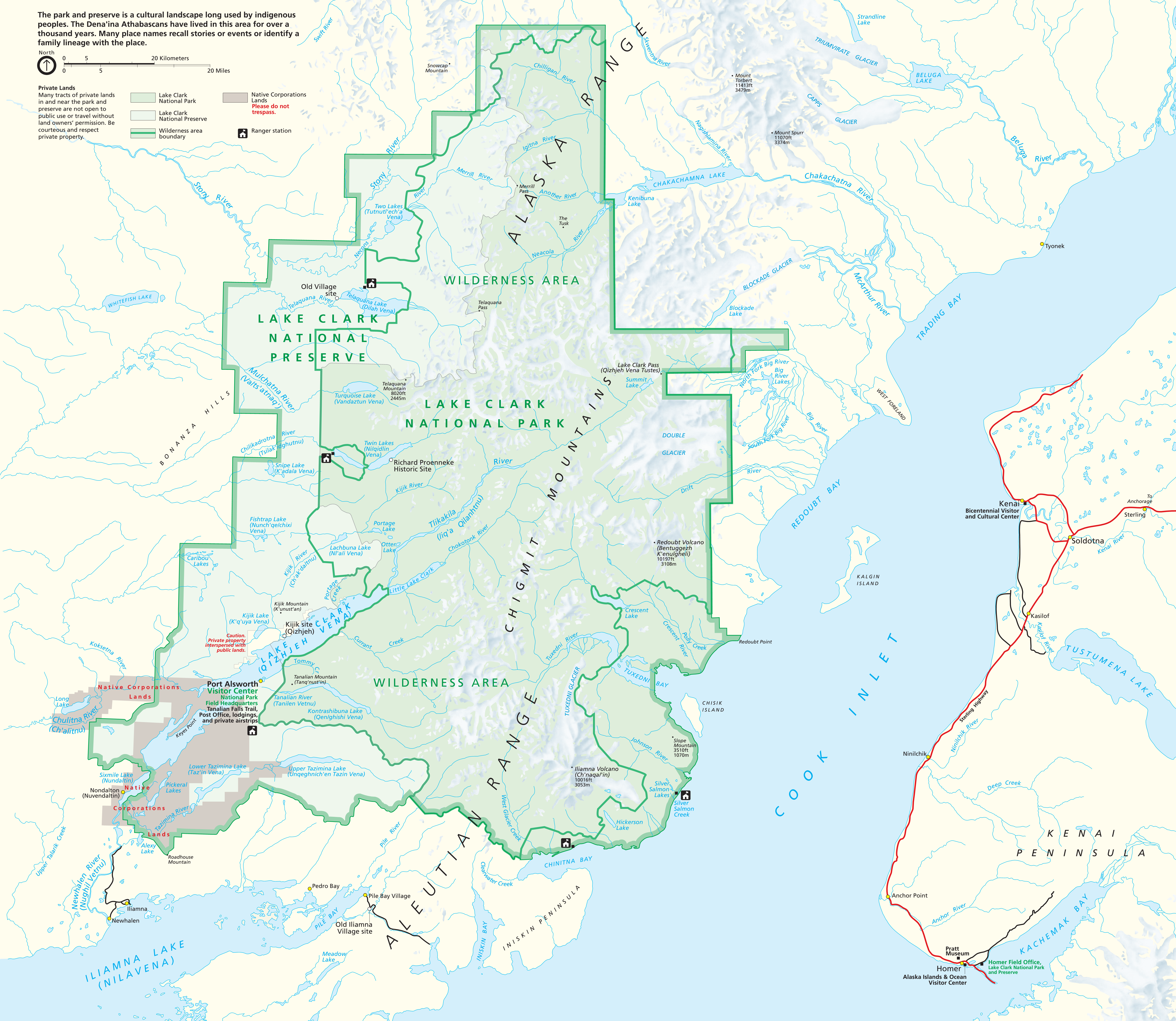

According to the National Park Service Land Resources Division summary listing of NP acreage (31/12/2015) [see here for statistical sources] Lake Clark NP&P covers a total area of 4,030,130.17 acres (1,630,936 ha) / 6,297 square miles (16,309 km2). Of this area 2,619,836.49 acres (1,060,210 ha) /4,093 square miles (10,600 km2) lie in the park and 1,410,293.68 (570,726 ha) / 2,204 square miles (5,708 km2) in the preserve.

As one of the top 10 US National Parks by size (most of the largest parks are in Alaska), Lake Clark NP&P is larger than the State of Connecticut, and nearly as large as Hawaii. It’s larger than the Everglades, Grand Canyon and Yosemite National Parks combined, but whereas these parks attracted a total of over 9 million visitors in 2014, Lake Clark NP&P saw just 16,100 visitors in the same period (and that was a huge increase over the 2013 figure of 13,000 visitors), so crowded it is not. There is just one residential community within the Park and Preserve, at Port Alsworth (population 159 at the 2010 census), which is located on the eastern shore Clark Lake, about 50 miles (80 km) from Crescent Lake.

The reason for the low visitor numbers is simply down to the fact that, apart from the coast, which can be reached by a comparatively long boat trip (and there are some powerful rips in Cook Inlet), if you’re going to visit the Lake Clark NP&P you’ll have to fly there. You can enlarge the above map as much as you want, but you won’t be able to find a drive-in route because there aren’t any roads there. There are barely even any maintained trails (except around Port Alsworth), and none where we were heading.

The coastal region of the park, in which Crescent Lake is situated, is just outside the officially demarcated “Wilderness Area”, but it all looked pretty isolated to me. There are a few Park Ranger stations (at Chinitna Bay, Port Alsworth, Silver Salmon Creek, Telaquana Lake and Twin Lakes), and, away from Port Alsworth, a few remote cabins and lodges for rent.

As you start to fly up the Crescent River you might notice a few ‘track lines’ in the trees to your left at Squarehead Cove. These are the remnants of a Crescent River logging project which stopped in 2002 after clear cutting about 700 acres of trees between 2000-2001. If you have a low level flight &/or great eyesight (take some binoculars) you might see the properties on the adjacent coastal strip of land first homesteaded by the Kroll family in the 1940’s, and which have been intermittently occupied by their descendants since that time.

As we flew up the course of the Crescent River, the mighty valleys that had only been hinted at the previous day were revealed…

…before we reached Redoubt volcano.

We flew on up the Lake Fork Crescent River and quickly reached Crescent Lake. What a difference a day makes.

The following technical description of Crescent Lake is taken from a USGS document:

“Land cover is primarily alpine tundra and bare soil (44%), spruce forest (31%), and permanent ice and snow (18%). Lake Fork Crescent River drains an area of 125 mi2. Notable features in this watershed are glaciers, which comprise about 16% of the basin and Crescent Lake. Crescent Lake is approximately 6 mi long and slightly more than 1 mi wide. The average depth of the lake is about 75 ft, and the deepest part is about 100 ft. The lake is oligotrophic; its open-water period lasts about 5 months – from June through October. Thermally, Crescent Lake is a dimictic lake – it circulates twice a year – in the spring and the fall. It is directly stratified during summer and inversely stratified during winter. Surface temperatures characteristically reach 10 to 12°C during the open-water period. Annual water-residence time or flushing rate is estimated to be 0.7 to 0.8 years. Most of the inflow comes from overland runoff and snowmelt. Inflow from definable streams consists of meltwater from glaciers on the southwest side of the basin, at mid-lake. The other major tributary is at the upper end of the lake. Because Crescent Lake is glacier-fed, the lake and its outflow have the characteristic turquoise colour. However, Crescent Lake does trap much of the suspended sediment that enters the lake. The North Fork Crescent River drains an area of about 75 mi2. Approximately 23% of the basin consists of glaciers. The North Fork channel is relatively steep, and during open water is characterized by the typical turbid colour of glacier-fed streams. The confluence of the North Fork and Lake Fork Crescent Rivers forms the mainstem of the Crescent River. In this section, the streambed channel becomes braided, and the channels constantly scour and shift.”

The above text reminds how short the floatplane fly-in period is, and how long the icy Alaskan grip on Crescent Lake endures, but it doesn’t describe how beautiful it is up there.

Taxiing over to the landing beach, the Cessna was turned out towards the lake, reverse thrust applied, and the pontoons grounded so that we didn’t even have to wet our feet on disembarking. We had arrived at Redoubt Mountain Lodge (RML) where we were first welcomed by the guard dogs K’eyush and Charlie (lodge security), and then by the friendly staff.

We were introduced to Colleen, our guide for the day, who we later learned was a fairly new and enthusiastic addition to the RML guiding team, having joined a couple of months previously after working as a volunteer with the US Peace Corps in warmer climes.

Boarding a comfortable and stable 4-stroke outboard-powered pontoon, we headed to the nearby southern shore of Crescent Lake, near the point where the lake flows out into the lower Lake Fork Crescent River.

If you fully enlarge the above image RML can just be seen to the left extent of the nearest tree line.

Manoeuvring backwards and forwards in parallel to the narrow beaches and shoreline scrub vegetation along just a couple of miles, we spent our time in the almost constant sight of bears, and were treated to a great range of their behaviours.

Fortunately for us, as it brings the bears out of the trees and scrub and into the water, Crescent Lake is one of the most productive Sockeye Salmon areas in the park. Between 1979 and 2012 (when they ran out of funding) the Alaska Department of Fisheries and Game used a sonar station located a couple of miles upstream from the Crescent River’s mouth to count returning fish numbers, and a fish wheel to determine the relative proportions of Sockeye to the smaller numbers of Pink, King, Chum and Coho Salmon, and Dolly Varden. Starting as early as the 15th June and ending as late as 12th August, the average count of returning Sockeye in the 33 years data was obtained in this period (no figures for 2009, but there was a small problem with Redoubt volcano erupting earlier that year) was nearly 73,000 fish per year swimming up the Crescent River.

“Is it a brown bear or a grizzly? The answer is that all grizzlies are brown bears, but not all brown bears are grizzlies. The grizzly is a North American subspecies of brown bear with the Latin name Ursus arctos horribilis. The correct scientific name for a grizzly is “brown bear,” but only coastal bears in Alaska and Canada are generally referred to as such, while inland and Arctic bears and those found in the lower 48 States are called grizzly bears.” [Source: PBS Nature Brown Bear Fact Sheet]

After about 2.5 hrs watching the bears we returned to the 5-acre bear protected Redoubt Lodge, as not only was our ride home ‘anchored’ there, but our trip also included a delicious lunch of an Alaska sized serving of fresh salmon.

I chatted with Tom about flying as a part of life in life in the Last Frontier “where 82 percent of communities have no road access, airplanes are used like pickup trucks and many young Alaskans learn to fly before they learn to drive”. With a state population of around 710,000 (2010 census) around 1 in every 60 Alaskans is a qualified to fly. He described the need for locals to be versatile in order to survive outside the brief tourist season. He and his wife were just setting up a new aquaponics venture, which it’s good to see seems to be doing pretty well, although I’m somehow not surprised.

It was all very unhurried and relaxed, but eventually it was time to depart. For our return flight there were two extra passengers in the shape of a young couple returning to Homer, and as there was no significant weight imbalances between us all, it was no problem when we volunteered to shunt backwards in the seating plan so that they might fully enjoy the sights we’d had coming in to Crescent Lake. That said, it wasn’t as though we weren’t able to enjoy some amazing views on the way back.

We flew on with views of Kalgin Island to our left and quickly reached the Kenai Peninsula once again, before travelling down the coast to Homer.

When we reached Homer, the aerial view was a stark contrast to that of the preceding day:

There isn’t much more to say than that we’d primarily travelled to Homer so that we could fly out to see Brown Bears in wild Alaskan territory, and, despite the proverbial weather hitting the propellers, we achieved that aim THANKS TO STELLER AIR!

Steller Air currently list two bear viewing day trip options: the trip we took to Crescent Lake, or a flight out to Brooks Camp, each of which is $650 per person.

In case you really can’t get a flight with Stellar Air (or you feel like you want a different type of bear viewing experience), other bear viewing operations flying out of Homer are as follows below. Listed pricing is as per company websites at time of posting, but check directly for updates. Check the minimum passenger numbers, any age limits just in case you’re travelling with young children, and deposit refund periods too. Research the locations used at the dates of your intended travel and look closely at the package details as there are some important differences in the offers, especially in terms of time spent at the destinations. If I were to book another bear viewing trip other than with Steller Air I’d invest in the cost of some international telephone calls to get a feel for the company.

- Bald Mountain Air Services fly two 10-passenger DHC3 Turbine Single Otter floatplanes to Katmai coastal river sites, Brooks River Falls, or Moraine Creek (in the north of the Katmai NP) depending on the time of year. Flights cost $675 per person 1st-30th June and 1st-15th It’s $695 per person 1st July-30th August. Again, there’s a small discount if you pay by cash or personal/travellers cheque – $25 per person – but, as you need to get a 50% deposit cheque to them within 30 days of booking, the same limitations as above are effective.

- Beluga Air is located next to Steller Air on Beluga Lake and fly with a 7-passenger DHC-2 Beaver floatplane. Most of the year they fly to the Katmai National Park (Brooks Camp, Crosswind Lake, Morraine and Funnel Creeks, Hallo Bay, Geographic Harbor, or Swikshak Lagoon) for bear viewing but also use Chinitna Bay and Crescent Lake. Prices appear to be on application.

- Emerald Air Service offer a guided day trip by 7-passenger DHC U-6A Beaver floatplane to an unspecified location which looks like it could be in the Katmai. $675.00 per person (credit card), $650 (cash, cheque or travellers cheque, but that presents the same deposit issue as Bald Mountain Air for non-US visitors). 50% deposit within 10 days of booking, remainder due upon travel. As mentioned near the start of this post, you can find them on Beluga Lake.

- Homer Air is the sister company to Smokey Bay Air, and offer bear viewing at either Lake Clark NP or the Katmai for $625 per person. They run 5-passenger wheeled Cessna U206G aircraft for beach landings from Homer airport.

- K-Bay Air (also running the same trips under the Alaska Bear Adventures brand [http://alaskabearviewing.com/]) offer three options: a “Short & Sweet Day Trip” at $589 per person, a “Classic Day Trip” at $695 per person ($670 per person for 4 or more), and a tailored Premium Day Trip, POA. There’s a $50 booking deposit and then payment is arranged in full. They run three 5-passenger wheeled Cessna 206 aircraft for beach landings from Homer airport.

- Smokey Bay Air offer bear viewing flights to Chinitna Bay, Silver Salmon Creek (Lake Clark NP), or Hallo Bay for $625 per person (min. 2 persons), 30% deposit on booking. Wheeled aircraft for beach landings. They also run 5-passenger wheeled Cessna U206F and U206G aircraft for beach landings from Homer airport.

More online information.

The Summitpost page for the Aleutian Range of mountains.

The Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADFG) web page for bear viewing in the Lake Clark National Park and Preserve.

Brown Bear information from the ADFG.

The US NPS web pages for Crescent Lake and the Brown Bears of the Lake Clark National Park. As is usual with the NPS, there’s lots of information here which is well worth looking at before you travel.

The 1988 NPS Final environmental impact statement: wilderness recommendation : Lake Clark National Park and Preserve, Alaska, with over 200 pages of information on the park’s wilderness designation. A little dated with regard to the then apparently unrecognised value of bear viewing, but lots of good background reading here, especially pages 26-44.

The IUCN Red List entry for global Brown Bear populations.

A 2003 NPS Water Resources Scoping Report for the Lake Clark National Park.

A 2006 USGS report on “Water Quality of the Crescent River Basin, Lake Clark National Park and Preserve, Alaska, 2003–2004” including notes on the impact of logging.