In the heat of a Croatian summer it pays to get up and head out as early as possible, which is why, at 07:20AM, we found ourselves in front of the gate of the Utvrda Peovica (Mirabela Fortress) in the Dalmatian Adriatic coastal town of Omiš. Here we discovered that the locals didn’t share our ideas.

![You can get to the entrance of the Mirabela Fortress by following the signs up a short 10-15 min. walk from the square where St. Michael’s Church (Crkva Sv. Mihovila) is located on Knezova Kačića in Omiš old town.]](http://www.afewmilesmore.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Utvrda-Peovica-Mirabela-opening-times-and-entrance-ticket-price.jpg)

We briefly returned to our nearby accommodation at Villa Mama before heading out again, this time to where our car was conveniently parked on the western bank of the Cetina River. At 07:44 AM it was already 27°C (80.6°F), but we didn’t have long with the air conditioning.

Taking Mosorska cesta north out of Omiš along the right bank of the Cetina and up the hairpin bends of the D70 for 4.1 km (2.5 mi.)/about 7 minutes, we then turned right onto the Z6165. Continuing along this road for a further 1.1 km (0.7 mi.) we passed through a short narrow tunnel (with priority to oncoming traffic) and reached our destination which was marked by a raised viewpoint with an iron fence.

Our new destination that morning was very specific, and this video from Crodrone captures the setting of the Mila Gojsalić memorial statue perfectly:

The story of Mila Gojsalić (also spelled “Mile Gojsalića”) is nearly 500 years old, and is set in the context of the tiny semi-autonomous ‘republic’ of Poljica standing against the might of the Ottoman Empire at the height of its power.

The history of Poljica is fascinating in its own right (see the links at the bottom of this post). For a people to successfully cultivate a viable, ordered living from this harsh landscape is no small feat. For such a small community to then continuously develop, define (with a series of formal statutes), and effectively defend (both by the political expediency of token suzerainty and armed resistance) a unique form of rural democracy largely on their own terms, for hundreds of years, is nothing less than remarkable.

However, in 1530 the future looked bleak. During the previous century the Ottoman Empire had expanded rapidly into Europe. In 1463 the Bosnian Kingdom had fallen to the army of Mehmed II in a matter of just a few weeks following the capture and execution of King Tomašević at Jajce, only 105 km (65.2 mi.) NNE of the Poljica village of Kostanje (named for its plentiful Chestnut trees) where Mila is said to have come from. The Ottomans created the sanjak of Bosnia, their westernmost province, from the central part of the conquered areas of Bosnia, and enlarged it further in 1482 when they took the Duchy of Herzegovina from the House of Kosača.

In 1493 the Ottomans had taken the Imotski fortress, 30 km (18.6 mi.) ENE of Poljica. Raiding further to the west, and less than 150 km (93.2 mi.) NW of Poljica, the Ottoman forces decisively defeated the combined troops of several Croatian nobles at Krbava Field, near Udbina, on the 9th September 1493, but for Poljica the threat of Ottoman expansion became reality when a “major Turkish detachment crossed the river Cetina into Poljica for the first time in 1500, taking one hundred and fifty people prisoner.” [See article by Edo Pivčević linked below]. Given that the population of Poljica at the time was only in the low thousands this would have been an almost unimaginable shock to the community. By 1502 Venice had ceded the Tvrđave Duare castle at Zadvarje at the south-eastern end of Poljica to the Ottomans and the threat, if not the reality of conflict, was a daily fact of life.

Ottoman forces finally seized the then political centre of Croatia at Knin in May 1522, with the downstream town of Skradin at the mouth of the Krka River (around 60 km (37.3 mi.) from the northern borders of Poljica) quickly following, but the inhabitants of Poljica had been on the receiving end of Ottoman ambitions for several years by then. By 1514 they had realised that the political strength of the coastal Venetian Empire would avail them little in defending their lands, and had already transferred their suzerainty to the Ottomans. It made little difference.

In 1526, and 313 km (195 mi.) NE from Kostanje, the Ottoman Empire, now under the leadership of Suleiman the Magnificent, had continued its northwards advance into Europe and inflicted a significant defeat over the Hungarians and their allies at the Battle of Mohács. Continuing north the Ottomans took Buda in 1529 before turning NW to lay siege to Vienna. This might sound to be a fair distance from Poljica but after Mohács the Ottomans started limiting the privileges given to Christians in captured territories unless they were to convert to Islam. With increasing dominance both regionally and locally, Mila would have been all too aware of threat to her community’s way of life from the Ottomans.

In the 1526 Poljica declined to pay the Ottoman tribute on the basis that the Turks had attacked the fortress at Klis, less than 5 km (3.1 mi.) NNE of Poljica, and a strategic gateway to Venetian Split. Led by Petar Kružić, men from Poljica had joined his Uskok defenders against the Ottoman attempt to seize Klis, but in 1530 the Ottomans turned their attention to Poljica more directly and invaded with an army of 10,000 soldiers. They are said to have burnt and looted their way through the villages of Srinjine, Tugare and Gata, before encamping near the latter settlement. This would have had particular symbolic significance as it was at the hill of Gradac, near Gata, that the people of Poljica would meet on St. George’s Day each year to choose their own leaders. The intention to subjugate Poljica could not have been clearer.

The Ottoman force was reportedly led by Herzegovinian Sanjak Ahmed Bey (more usually reported as ‘Ahmed-pasha’ or sometimes ‘Osman-pasha’), but he would meet his match in Mila Gojsalić.

Remembered in popular memory as a notably attractive young lady of the district, accounts vary as to whether Mila Gojsalić was seized by her enemy and taken to Ahmed-pasha’s tent where she was raped (the most oft repeated story), ‘sold’ alongside other women of the district to the invaders and then raped, or whether she used her charms to ‘infiltrate’ the emplacement and seduce the leader of the Turkish forces.

Whatever the circumstances, she is said to have waited until the Ottoman leader was asleep and crept out from his tent, before setting fire to the encampment. The blast from the ignited powder store is said to have killed him together with many other officers and soldiers. In some versions of the story the explosion is said to have also claimed Mila, whilst in others she is said to have leapt from a cliff to avoid being captured by her enemies.

The disarray among the Ottoman invaders was such that the people of Poljica were able to strike with decisive force in the darkness and overrun their erstwhile oppressors, many of whom, the story tells, were forced over the edge of the precipice where the Mila Gojsalić memorial statue is located today.

This was not the end of the fight for Poljica, but Mila was not forgotten by her people, and, in time, she became recognised as a Croatian national folk hero. In recent years her home village of Kostanje has hosted the “Dani Mile Gojsalić” (Mile Gojsalić Days). 2016 will be the 13th edition and will run from the 14th – 17th July. You can follow the event (in Croatian) on the organisers’ Facebook page.

Our day continued with a drive on through Kostanje, crossing the valley over the Cetina on the old Pavica Most, and on to Zadvarje. From here we headed inland to visit the famous sinkholes at Imotski, and returned via a stop at the stecći near Lovrec.

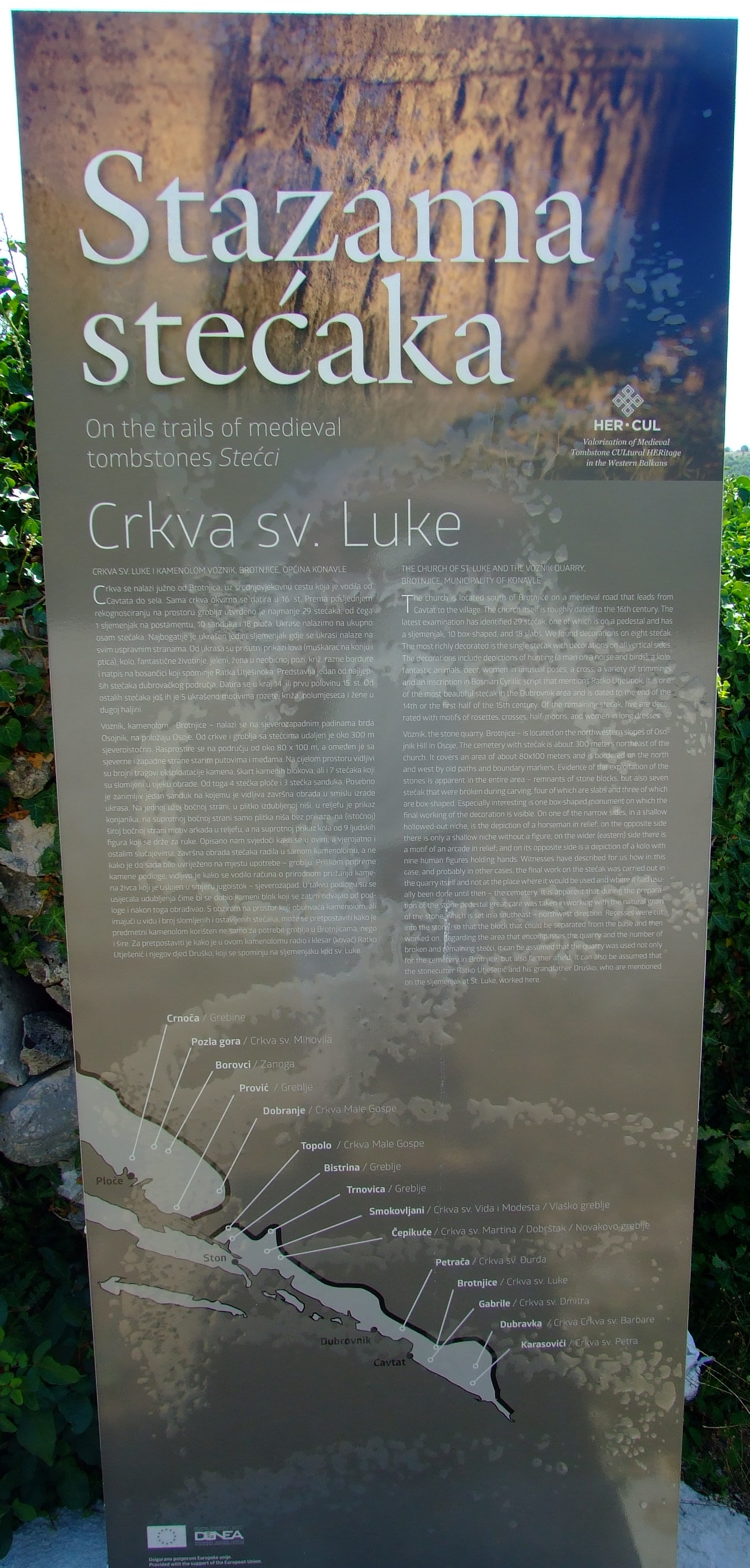

By the early evening we were back in Omiš where we retraced our steps through the now much busier streets to the Utvrda Peovica (Mirabela Fortress). This time it was open to visitors.

It is believed that work on this redoubt was started early in the 13th century during the period when Omiš was ruled by the Kačić family who are perhaps best known for their tenure during the period when the famed Omiš pirates used the tower as a lookout for passing prey. Built on six tumbling tiers, the Venetians expanded and refortified the structures after taking over in 1444.

Because of the acoustic dynamics of the Mirabella’s location sound can be amplified without being directionally attributable. This strange feature was used to advantage by defenders facing an Ottoman attack in 1537. Shouting loudly, a relatively small number of soldiers were able to convince the invaders that the town contained a large force in wait for them, and, according to legend, the Ottoman troops promptly retreated.

As we were on a road trip vacation tour we only spent a couple of nights and one full day in the Omiš area. The mid-summer heat was, to say the least, a limiting factor on our exploration of the town and wider region, but I don’t regret that we made the small effort to visit the Mila Gojsalić memorial statue and the Mirabela. If I were to return with anyone who hadn’t seen these views I wouldn’t hesitate to take them there, and I think that, with more appropriate weather conditions, I would easily be able to spend a minimum of a couple more days exploring the area out on foot.

There is one final consideration that would almost certainly get me to spend a night in Omiš if travelling down the Dalmatian coast. Its name is the Konoba Joskan. On the night of our arrival in Omiš we quickly confirmed that many of the choices for eating out in the centre of the old town, and the vicinity of our accommodation, involved a ‘public dining’ experience.

The Konoba Joskan is located up an opening on the north side of Knezova Kačića, and if at first you manage to miss the entrance to this restaurant just keep looking (or asking) until you find it. Previous vacation research and the idea of a small enclosed and more intimate konoba courtyard had already caught our attention, but we were unprepared for just how good this place would be.

Given that it was the height of the tourist season, we were lucky enough to be reasonably early and get a table in the courtyard (there’s also an inside air conditioned dining area), but that said, we noticed that the lovely staff bent over backwards to fit in later arrivals without a reservation.

The simple two-page menu suggested ‘fresh daily’ (which was confirmed when the day’s fish options were explained), and my wife and I both opted for a fillet steak with sliced fried potatoes and a shared tomato salad in oil and balsamic vinegar, with a couple of beers. It was the best meal we had eaten in Croatia to date. In fact, it was so good that we went back the next night, after our sight-seeing tour, when we ordered exactly the same meal. It was just as good the second time round, and therefore qualified it as one of the two best meals we had in Croatia.

More online information.

For the history of Poljica take a look at “The Principality of Poljica From its Medieval Inception to its Fall in 1807” by Edo Pivčević.

The history page from the village of Sitno website provides another brief introduction, as does cuvalo.net which adds a legal commentary and translation of the Poljica Statutes.

There’s also “Split and Poljica – relations through history” by Prof. Mate Kuvačić. It is in Croatian, but Google translate works reasonably and is worth a read.

Later additions.

Take a look at these views from a beautiful January walk by BBQboy in January 2017.